Between the years 1840 and 1900, the railroad system fundamentally transformed space and time in Columbia County, New York, such that county residents entirely reorganized their spiritual and communicative lives in adjustment. Just as it had “annihilated space and time” seemingly everywhere it went, here the development of the railroad system did much the same.1 As the Hudson River, Hudson and Boston, and New York and Harlem lines each successively expanded throughout the county, they brought with them ideas, technologies, customs, and people from afar, confirming what county residents had already begun to sense: that the world was coming to meet them in their corner of New York. The railways had a profound impact on the public institutions of the time, and as such, on the development of the public sphere, or the “social totality,” in Columbia County. This project begins the work of examining the “transformation of social relations, their condensation into new institutional arrangements, and the generation of new social, cultural, and political discourse around this changing environment” by examining where and when these institutions sprang up, and posits that a spatial understanding of their emergence, colocation, and interaction would open up new lines of inquiry into how and why New Yorkers organized and experienced these transformations.2

In mapping area post offices, newspapers, libraries, and churches throughout the railroad era in Columbia County, this project combines methodologies taken up by several key scholars and groups at the forefront of historical geography and digital history. In particular, “The Geography of the Post” by Cameron Blevins; Lincoln Mullen’s work around mapping slavery and American religious history; the Library of Congress’s historical newspaper project, “Chronicling America”; Stanford University’s Spatial History Project and, specifically, its suite of projects around the American railroad network and westward expansion, “Shaping the West”; the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s “Railroads and the Making of Modern America”; Gregory P. Downs and Scott Nesbit’s “Mapping Occupation“; and Sonia Shah’s “Mapping Cholera” all contributed to the conception and approach of “Assembly and Association” as an historical investigation enhanced by its geographic focus. This study shares with these and other digital history projects a focus on establishing a technical environment and “framework…for people to experience, read, and follow an argument about a major historical problem,” while leaving space for such readers to arrive at their own interpretations about the material, thus taking part in the kind of interactive analyses and “collective work” that “[undergird] the production of historical knowledge.”3 This study was also inspired by the work of Anne Kelly Knowles, Tim Cole, Al Giordano, and the other scholars who contributed to the “Geographies of the Holocaust” project, which uses spatial analysis to offer new insights and raise further questions about this dark period; the result is a group of case studies and visualizations that shed light on the role space played in the experiences of the victims and the decision-making of the perpetrators. “Geographies of the Holocaust” illuminates our understanding of an otherwise well-studied period and thus makes a forceful argument for the value of applying methods from the field of geography to enhance historical studies. In this vein, “Assembly and Association” argues that the history of the development of Columbia County’s public sphere in the 19th century, as evidenced through the growth of the select public institutions listed above, is fundamentally spatial.

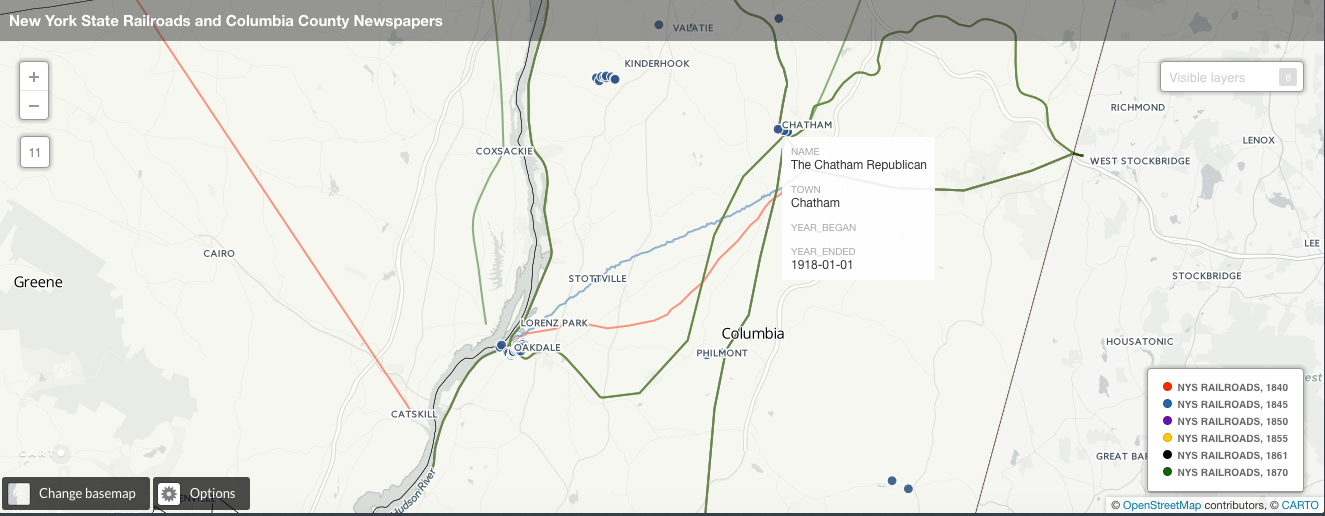

To begin with, there was a lively newspaper business in 19th century Columbia County, indicating that there was a highly literate audience that was hungry for news, as well as a thriving advertising market. Each of the 68 newspapers published during this time came from a town or city situated along a rail line; Hudson, Chatham, and Kinderhook, important commercial centers and railway junctures each, published between 59 and 62 of these 68 titles, indicating that news traveled in straight lines along railways and telegraph lines. Similarly, libraries built during this period went up in towns with rail stations. This suggests that the free and democratic ideals underpinning public libraries were associated with the railways just as much as the commercial newspaper business. The space opened up by the railroads was seen as conducive to both the free exchange and scholarly pursuit of ideas and the competitive sale of printed information. In the end, county residents received a great deal of their news and textual information from sites inescapably tied to the railways.

Map showing Columbia County newspapers published during the 19th century, and the railroad lines that ran through the area.

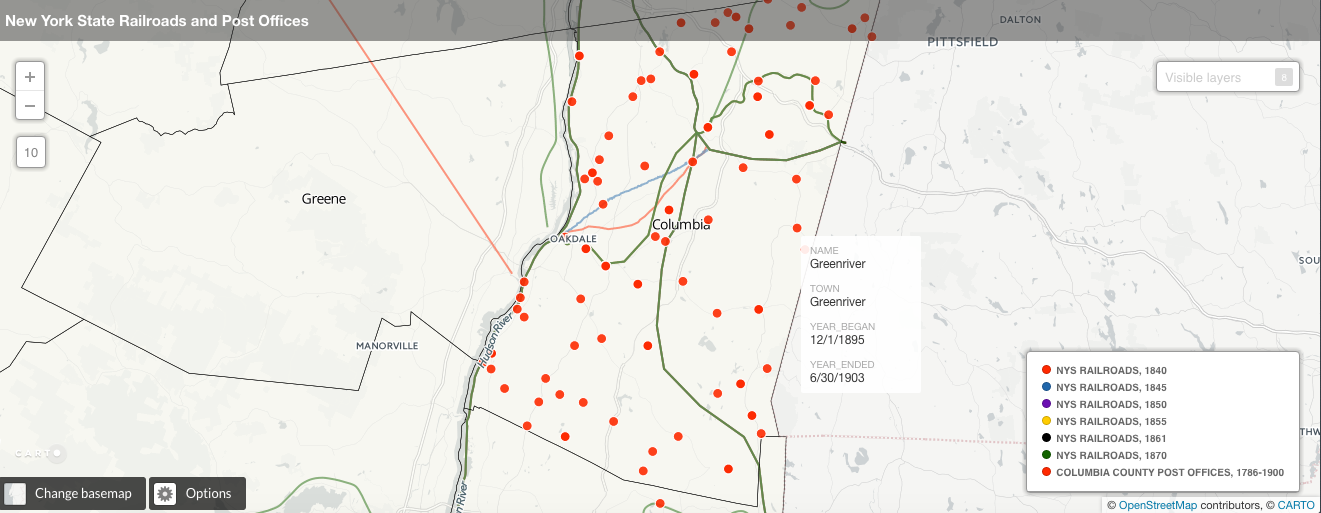

Conversely, Columbia County tended to build post offices in the spaces between railroad lines and stations, along extant roads that connected towns, villages, and cities in ways that the rails did not. Even though the post here witnessed a significant increase in the number of post office buildings during the railroad era–82 of the 127 raised between 1786 and 1900 were built after 1840–many were positioned so as to transcend the communication pathways afforded by the railroad system. Thus residents read, wrote, produced and received texts, and otherwise engaged in communicative acts in a variety of ways, either along or across railway and telegraph lines, that nonetheless were mediated by these new technologies.

Map showing Columbia County post offices built in the 19th century in relation to area railroad lines.

Finally, religious statistics about the number and kind of church that dominated the spiritual landscape of 19th century Columbia County, that of the Methodists, points once more to the influence of the railways. Mirroring larger national trends, the Methodist church expanded at a rate that far outpaced rival faiths during this period: taking into account data from the 1850, 1860, 1870, and 1890 United States Censuses, when the government recorded such religious information, the number of Methodist churches in the county went from 19 in 1850, to 34 in 1860, 35 in 1870, and 39 in 1890. Likewise, the number of parishioners that all Methodist churches taken together could accommodate swelled across these censuses from 6,375 in 1850, to 7,760 in 1850, and 12,000 in 1870, before dropping slightly in the 1890 census to 11,285. The total value of Methodist church property in the county rose as well, from $26,480 in 1850 up to $201,200 by 1890.4 Methodist dominance in Columbia County must be understood in terms of the psycho-spiritual effects that the railroad and, by extension, modern technology had on the people and the landscape. As the railways brought the outside world into Columbia County, collapsing time and space, this both threatened the moral order that pious Christians struggled to affirm while simultaneously offering an ever-expanding realm of potential converts. Methodism, with its public rituals of revival meetings and conversions, inclusiveness, and sentimental brand of Christianity, was positioned to address these changes perfectly by dividing the world into two spheres: that which must be protected within the Methodist household or community, and that which called out for spiritual rescue and conversion. This “dialectic of evangelical identity,” as A. Gregory Schneider terms it, is a unique byproduct of and solution to the social and cultural changes ushered in along the railways, and helped contribute to Methodism’s rise during this period.5

This thesis shows that in 19th century Columbia County, New York, space was a significant factor in the development of the public sphere via its public institutions. With the expansion of the railroad system came a reordering of space and place, which had a decisive impact on how county residents organized their spiritual and communicative lives and the makeup and vision of the various publics with which residents interacted.

End Notes

1. Wolfgang Schivelbusch,. 1986. The Railway Journey. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. pp. 33-44.

2. Michael Warner, 2002. “Publics And Counterpublics (Abbreviated Version)”. Quarterly Journal Of Speech 88 (4): p. 413. doi:10.1080/00335630209384388; Geoffrey Eley, 1990. “Nations, Publics, And Political Culture: Placing Habermas In The Nineteenth Century.”. Presentation, Program in Social Theory and Cross-Cultural Studies, University of North Carolina. Conference on “Habermas and the Public Sphere.” September 8-10, 1989. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/51184

3. Douglas Seefeldt and William G. Thomas III, 2009. “What Is Digital History?”. American Historical Association. https://www.historians.org/publications-and-directories/perspectives-on-history/may-2009/intersections-history-and-new-media/what-is-digital-history; Daniel J. Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig, 2005. Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web. George Mason University Center for History and New Media. http://chnm.gmu.edu/digitalhistory.

4. “Minnesota Population Center”. 2016. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0. Minneapolis, MN: University Of Minnesota 2011. http://nhgis.org.

5. A. Gregory Schneider, 1990. “Social Religion, The Christian Home, And Republican Spirituality In Antebellum Methodism”. Journal Of The Early Republic 10 (2): pp. 179, 184. doi:10.2307/3123556.