This project seeks to investigate the development of the public sphere in New York State during the rapid expansion of railway transportation from the middle- to the late-19th century. By public sphere, I mean to consider Jürgen Habermas’s conception of

a realm of our social life in which something approaching public opinion can be formed. Access is guaranteed to all citizens. A portion of the public sphere comes into being in every conversation in which private individuals assemble to form a public body…Citizens behave as a public body when they confer in unrestricted fashion–that is, with the guarantee of freedom of assembly and association and the freedom to express and publish their opinions–about matters of general interest. In a large public body this kind of communication requires specific means for transmitting information and influencing those who receive it.1

In addition, Michael Warner’s take on “the public” is here a useful addendum to Habermas’s argument. In answering the vexing question of “What is a public?”, Warner notes that this “is a curiously obscure question, considering that few things have been more important in the development of modernity…[and given that] publics have become an essential fact of the social landscape, yet it would tax our understanding to say exactly what they are.” Though he focuses mainly on publics “in relation to texts and their circulation,” still he posits that “the public is a kind of social totality [whereby] its most common sense is that of the people in general,” while “a public can also be a second thing: a concrete audience, a crowd witnessing itself in visible space.”2 In other words, in order to investigate what a public is and how it develops, one might try to understand how certain people come together, communicate, form opinions and convey them, and attempt to influence one another.

Spurred on by the work of Alfred D. Chandler, Jr. and Wolfgang Schivelbusch, who assess the economic and cultural effects of the railroads;3 Cameron Blevins’s geospatial analysis of the post office in the 19th century American West, “Geography of the Post”; the Spatial History Project’s “Shaping the West”; data and visualizations from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s “Railroads and the Making of Modern America”; and Lincoln Mullen’s work to gather, organize, and map data about the religious history of the United States, this study seeks to gather and present information about the proliferation of railway stations and select public institutions between 1840 and 1900, when railroad construction in New York State was at its apex, before consolidation under the New York Central Railroad and eventual obsolescence.4 By charting the spread of libraries, newspapers, post offices, and churches in Columbia County, NY, during this period, this project seeks to serve as a prototype for combining elements from each of the abovementioned scholarly studies on a regional scale; that is, to afford users a view into the regional development of the public as understood by Habermas and Warner.

What are the connections between the development of the railway system and a contemporaneous “free market religious economy” that witnessed the rise of “upstart” sects in America,5 or the proliferation of newspapers and instantiation of rural public lending libraries, or the growth of the US Postal network? This project begins the work of examining the “transformation of social relations, their condensation into new institutional arrangements, and the generation of new social, cultural, and political discourse around this changing environment” by examining where and when these institutions sprang up, and posits that a spatial understanding of their emergence, colocation, and interaction would open up new lines of inquiry into how and why New Yorkers organized and experienced these transformations.6

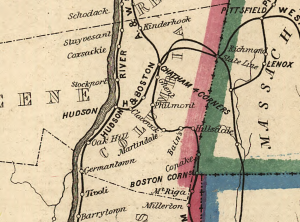

Columbia County, New York, offers a rich microcosm of activity during this time period in which to examine the development of the public sphere. Situated between New York to the south, Albany and onward to the Erie Canal to the west, and commercial points east such as Worcester and Boston, rivertowns along the Hudson River and inland stretching to the Berkshires had been market centers for as long as settlers inhabited the Hudson Valley. Indeed, the city of Hudson itself had been a “burgeoning port” for goods traveling along the river for decades, while Chatham served as an important link between New York and New England commerce; what was becoming increasingly evident, however, was that there was an “urgent need for a better method to connect” river towns and cities with their inland counterparts.7 Beginning with the Hudson and Berkshire Railroad, which was chartered in 1828 and completed in 1838, and ending with the construction of the county’s last rail stations in 1905, Columbia was eventually “crisscrossed by a labyrinth of rails…owned by and operated under a confusing and often changing array of corporate names,” before eventually becoming consolidated under the aegis of Cornelius Vanderbilt’s vast New York Central Railroad network. While the “first railroad boom…[of the] late 1840s and 1850s”8 saw the chartering and construction of a number of stations and depots, Columbia County continued to develop its railways throughout the rest of the 19th century until it was firmly established as an important transportation hub joining New York’s downstate metropolis, capital city, and commercial markets on both sides of the Hudson river.

Taken from Thomas Petingale’s 1858 map of New York State railroads.9

At the same time, America was emerging from the shift from traditional denominations such as the Congregational, Episcopalian, and Presbyterian faiths to evangelical Protestantism that characterized the first half of the 1800s. The so-called Second Great Awakening saw the “upstart sects” of Baptism and Methodism rise to prominence, outpacing competing religions, old and new, for membership and centrality in American spiritual life. At the heart of both faiths was a robust populism: as they “succeeded in recruiting more people to their churches with an informal, popular vernacular style…preachers increasingly claimed that formal training and formal worship were inhibitions to the Gospel and that the common person with Bible in hand was a more reliable guide to authentic Christianity.”10 Citing US Census data, Finke and Stark note that as a percentage of all total religious adherents, between 1776 and 1850, Baptists increased their share from 16.9% to 20.5%, while Methodists rose from 2.5% to 34.2%.11 Though only two of the many growing evangelical Christian faiths during this era, Baptism and Methodism were by far the standout denominations. In all, by the mid-1850s, what “began as antiformalist competitors to the main colonial churches” succeeded in calling to worship some 40 percent of the nation’s population, or 10 million people.12 In Columbia County, Methodist churches in particular dominated the spiritual landscape: according to US Census data from the NHGIS, for the years 1850, 1860, 1870, and 1890 (the only years between 1840 and 1906 that this information was captured by the census) the number of Methodist churches in the county rose from 19, to 34, 35, and 39, while Baptist churches actually declined from 10 to 9 to 7 in the same period.13 This domination might be attributed to Methodism’s focus on building a “social religion,” one which taught that through lively participation in public rituals of worship–revival meetings, conversions, singalongs–individuals would find salvation among a like-minded community of worshippers.14 The evangelical faiths embraced revivalism, the notion that they could “usher in a new age of the spirit,” as a core tenet, and extended this interpretation of Christianity into camp meetings, Bible study classes, church organizations, voluntary societies, and volumes of literature espousing their beliefs. “Intimate fellowship” was achieved through these institutional hallmarks, helping to democratize American Christianity in unprecedented ways.15

In short, Methodism utilized public, highly visible, and inclusive spiritual experiences to engage its followers and attract new worshippers; its success in expanding throughout Columbia County during this period, following larger national trends, suggests that in this area Methodism found a receptive audience that was eager to embrace and be embraced by a different form of Christianity. Moreover, as mid-century Columbia County underwent radical changes on account of the railroad’s inexorable march across the landscape, residents likely turned toward’s Methodism’s “dialectic of evangelical identity” for solace and guidance: just as the world both expanded and contracted due to new transportation (the railroad) and communication (the telegraph) technologies,16 so too did devout Methodists seek to retreat from the encroaching “impious ethos” of the world brought to their doorstep by these new technologies even while rhapsodizing about how to go out and save this world through conversion.17 For a geographic space and a people engaged in the fundamental struggle of modern times–how to maintain the soul even as the machine interposes itself–Methodism must have seemed particularly well-suited for their needs.

The middle decades of the 19th century also marked the expansion of the US postal network, which during this period “developed the most elaborate distribution system then existing in the country” that was seen as “absolutely critical in creating channels of communication, commerce, and personal contact required for a connected civilization.” Nationally, between 1790 and 1860, as Mark Noll shows, the number of post offices increased from 75 to 28,498;18 in Columbia County, NY, between 1786 and 1900, 127 post offices were built.19 The frequency with which new post offices were built here relates to the construction of area the railroads: between 1786 and 1839, 45 post offices were built in Columbia County; during the railroad era, from 1840-1900, fully 82 post offices went up in the county. And yet, county residents built post offices primarily in the spaces in between rail lines, or, in other words, municipalities where there were no rail stations and attendant telegraph centers. As the 19th century world came crashing into Columbia County along these lines of communication and transportation, the distribution of post offices suggests that the reading and writing public here strove to articulate discursive spaces via the post apart from those afforded by these new technologies.

Finally, Columbia County witnessed changes in its reading public as evidenced by a marked increase in the number of newspapers its residents published and the instantiation of public lending libraries. According to the “Chronicling America” project, run by the Library of Congress and the National Endowment for the Humanities, 53 newspapers began their print runs between 1840 and 1905; by comparison, for the period between 1792 and 1840, Columbia County managed to publish only 14 newspapers.20 The proliferation of newspapers points to a number of crucial developments when considering the growth of the public sphere: first, that Columbia County was highly literate; second, that there was interest enough in print culture as a medium to sustain so many newspapers; third, the towns that comprised Columbia County saw themselves as inhabiting voices and points of view important enough to speak on their own behalf; finally, that despite the focus on local voices and interests that such papers undoubtedly carried, whether they were “functional,” political, or religious,21 Columbia County’s print apparatus was tied to the “emerging mass culture” beyond the county line through the developing railway and postal networks. As Ronald Zboray notes,

Perhaps the greatest impact of the railroad upon the antebellum reader concerned the nature of American community life. Areas well-served by rail, such as the Northeast, experienced a veritable flood of printed information, a new nationally oriented mass culture to compete with the standing local culture. Low postage rates for newspapers encouraged this flood.22

In the wake of this proliferation of newspapers, Columbia County took steps to expand its reading public further by chartering and building public lending libraries. Columbia County is allegedly home to the nation’s “first free public library,” founded in New Lebanon in 1804,23 and by 1905 there would be 3 others serving the growing reading public. Extrapolating from Tom Glynn’s study of the early history of the New York Society Library, we might locate within the development of public libraries “a trend toward a broader, more inclusive conception of the public and a more democratic conception of public authority.”24

By studying and mapping the growth of the railroad network, popular ascendent faiths, post offices, newspapers, and public libraries, this project endeavors to chart the evolution of the public sphere in Columbia County, NY, in the mid-late 19th century.

End Notes

1. Jurgen Habermas, Sara Lennox, and Frank Lennox. 1974. “The Public Sphere: An Encyclopedia Article (1964)”. New German Critique, no. 3: 49. doi:10.2307/487737.

2. Michael Warner, 2002. “Publics And Counterpublics (Abbreviated Version)”. Quarterly Journal Of Speech 88 (4): 413. doi:10.1080/00335630209384388.

3. Alfred D. Chandler, 1977. The Visible Hand. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press; Alfred D. Chandler, 1965. The Railroads, The Nation’s First Big Business. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World; Wolfgang Schivelbusch,. 1986. The Railway Journey. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press.

4. Cameron Blevins,. 2015. “Geography Of The Post”. Cameron Blevins. http://cameronblevins.org/gotp/; “Shaping The West”. 2016. Spatial History Project. https://web.stanford.edu/group/spatialhistory/cgi-bin/site/project.php?id=997; Lincoln A. Mullen, “Digital Projects.” Blog. Lincoln Mullen. http://lincolnmullen.com/#digital-projects;

5. Roger Finke and Rodney Stark. 2005. The Churching Of America, 1776-2005. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press. pp. 54, 71-108.

6. Geoffrey Eley, 1990. “Nations, Publics, And Political Culture: Placing Habermas In The Nineteenth Century.”. Presentation, Program in Social Theory and Cross-Cultural Studies, University of North Carolina. Conference on “Habermas and the Public Sphere.” September 8-10, 1989. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/51184. p. 2.

7. A.S. Callan, Jr., 2002. “Memories Of The Old H&B RR”. Columbia County History & Heritage (1:2). Kinderhook, NY: Columbia County Historical Society. p. 3.

8. Chandler 1977, p. 82.

9. Thomas Petingale. Map of the rail roads of the state of New York showing the stations, distances & connections with other roads; Thos. Pentingale, L.P. Behn. Buffalo, N.Y, 1858. Map. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/98688523/.

10. George M. Marsden, 1990. Religion And American Culture. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 64.

11. Finke and Stark, p. 54.

12. Mark A. Noll, 2002. America’s God. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 197.

13. Minnesota Population Center. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota 2011.

14. A. Gregory Schneider, 1990. “Social Religion, The Christian Home, And Republican Spirituality In Antebellum Methodism”. Journal Of The Early Republic 10 (2): 163-189. doi:10.2307/3123556. pp. 170-171.

15. Finke and Stark, pp. 72-73.

16. Schivelbusch, pp. 34-35.

17. Schneider, pp. 170-171, 180.

18. Noll, p. 200.

19. John L. Kay and Chester M Smith. 1982. New York Postal History. State College, PA: American Philatelic Society. pp. 76-80.

20. “Chronicling America « Library Of Congress”. 2016. Chroniclingamerica.Loc.Gov. http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/.

21. Mike Esbester, 2009. “Nineteenth-Century Timetables And The History Of Reading”. Book History 12 (1): 156-185. doi:10.1353/bh.0.0018. pp. 159-164.

22. Ronald J. Zboray, 1988. “Antebellum Reading And The Ironies Of Technological Innovation”. American Quarterly 40 (1): 65. doi:10.2307/2713142. pp. 76-77.

23. “About At New Lebanon Library – New Lebanon, NY”. 2016. Newlebanonlibrary.Org. http://newlebanonlibrary.org/about-us/.

24. Tom Glynn, “The New York Society Library: Books, Authority, and Publics in Colonial and Early Republican New York.” In Reading Publics: New York City’s Public Libraries, 1754-1911. 17-42. New York: Fordham University Press, 2015. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1287fsn.5. p. 17.